Table of Contents

1871–1874: Kingdom of Fiji, Ma‘afu vs Cakobau, and the Last Steps to Cession

Before Fiji became a British colony in 1874, it briefly existed as the Kingdom of Fiji (1871–1874) under Ratu Seru Cakobau. The “kingdom” was fragile—part bold experiment, part settler contrivance—trapped between chiefly rivalries, Tongan influence under Ma‘afu, and the ambitions of planters and missionaries. These tumultuous years explain why Fiji’s leaders chose cession: a desperate bid to stabilise a fractious archipelago. For Indo-Fijians, the kingdom years matter because they created the political vacuum that soon drew in the British Empire—and with it, the indenture pipeline that began in 1879.

Confederacies, Missionaries, and the Planter Frontier

Long before 1871, Fiji’s major confederacies—Bau, Rewa, and Cakaudrove—competed for maritime power, tribute, and alliances. The rise of Christian missions (Wesleyan/Methodist, Catholic) reshaped chiefly politics, while European beachcombers and planters nudged Fiji into the Pacific’s commercial circuits (sandalwood, bêche-de-mer, coconuts, cotton). The American Civil War had briefly inflated cotton prices, helping settlers claim land and labour on dubious deeds. Violence, debt claims, and inter-island feuds proliferated.

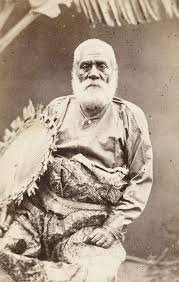

Into this combustible mix stepped Ratu Seru Cakobau (Bau), a formidable warlord-statesman who sought to centralise rule. But there was another power: Ma‘afu of Tonga, whose military reach and diplomacy across Lau and eastern Fiji turned him into the second pole of authority. As settlers multiplied and debts mounted—including the notorious US claim for compensation over earlier incidents—Fiji drifted toward a crisis with no referee.

The 1871 “Kingdom”: Bold Idea, Weak Foundations

With missionary and settler encouragement, Cakobau proclaimed a Kingdom of Fiji in 1871—complete with a legislature largely influenced by Europeans, a nascent bureaucracy, and grand titles. On paper it promised order and foreign recognition; in practice the kingdom struggled to tax planters, police the seas, or prevent private militias from settling scores. Land claims were chaotic, justice uneven, and armed clashes frequent.

Ma‘afu remained a counterweight: he commanded respect in Lau and held strong ties to Tonga, checking Bau’s ambitions. Meanwhile, planters—some respectable, others freebooters—pursued labour by coercive recruitment from other islands (the “blackbirding” era) and agitated for a strong protector who could guarantee property, labour supply and export stability. The kingdom was not delivering that security.

Why Chiefs Chose Britain

By 1873–74, collapse loomed. The kingdom had become a magnet for international complications: American debt demands, French and German commercial interests, Tongan influence via Ma‘afu, and settler pressure for a formal empire to underwrite their ventures. Missionaries feared moral anarchy; chiefs feared losing control to militias and creditors. The result was a remarkably pragmatic decision: offer Fiji to Britain.

On 10 October 1874, Cakobau and allied chiefs signed the Deed of Cession at Levuka. Britain promised lawful government, a check on settler excesses, and recognition of chiefly authority over “native affairs.” That bargain created the colonial framework that, five years later, opened Fiji to indentured labour from India.

Why These Years Matter to Indo-Fijians

For Indo-Fijians, the 1871–74 passage explains the “why” behind Girmit. Colonial order stabilised the planter economy and protected indigenous land from freehold alienation—yet it also created the labour vacuum that Britain filled with Indian indenture from 1879. The triangular bargain—chiefly autonomy in native affairs, settler security, and imperial rule—left little space for the rights of a future Indo-Fijian community. That exclusion would define the political battles of the next century: franchise, land, unions, and citizenship.

Legacy

The kingdom’s brevity does not diminish its significance. It was Fiji’s first modern state-building attempt and the hinge on which colonial Fiji swung into being. It also framed the long story that followed: a protected indigenous land regime, an imported labour force, and a settler economy under imperial law. When Indo-Fijians later fought for common roll, equal citizenship, and fair cane contracts, they were pushing against structures set in motion in these final pre-cession years.